Monday, October 24, 2011

Shades of Blue: Is there a European alternative to the Brussels project?

The post is from October, but the issue looks increasingly relevant.

As the EU struggles with its own well-documented problems, the UK has tied itself in knots by choosing today to debate and vote on the idea of a referendum on EU membership which is unlikely to happen after all three major parties put a three-line whip on the issue to vote down the proposal, which was triggered by the same pesky government e-petition website that threatened to throw open the debate on capital punishment.

British Eurosceptics are not a homogeneous group. There are the rabid 'bent banana' Eurosceptics who ignore the geographical reality of where our island sits, and for whom there is no distinction between EU migrant workers and illegal immigrants from elsewhere in the world. There are still some with delusions about the UK's potential global role, or farcical ideas that Americans or Australians would be 'delighted' to open up to preferential economic agreements with the UK. There is the frequently-coined argument that when Britain voted in the 1970's it voted to join an economic union, not a political one, but a look at the founding treaties of the EU makes clear that it was all along a politically-coloured project. Then there are quite reasonable arguments made about the democratic deficit in the EU's institutions. There is also the technical constitutional argument, which relatively few mention but which holds some water, about the incompatibility of the EU's system with the British system, that the British constitutional principle that 'no parliament can bind its successor' is broken by the signing of European treaties.

The main argument being given against the EU referendum seems to be 'now is not the time', which means that the issue in the long term is not likely to go away. Many people will continue to support Britain's withdrawal, saying things like 'look at Norway'. A Norwegian local politician I met a couple of years back however lamented her country's unwillingness to join the EU, saying that Norway has to implement 95% of EU legislation, with a 0% say about what goes into it. Very few who truly understand the issues think that Britain can simply have no form of economic integration with the EU. If Britain, for example, was to leave the EU, but desire to continue to participate in the single market, it would have to accept something similar to the EEA deal. Switzerland, on the other hand, has a series of bilateral opt-ins and opt-outs of EU policies, but on many issues it is captive to the regime that surrounds it.

Britain, Norway, and Switzerland are not alone in feeling that their deals with Brussels are in some way unsatisfactory. Across Europe, on the eastern frontier, we have Turkey, the candidate country which may never join, which so far has only a customs agreement with the EU which is of limited value. Then there is Ukraine, which, whilst doing its best to shoot itself in the foot, has not yet formally abandoned its deep free trade area talks with the EU. Georgia and Moldova are likely to agree similar free trade deals with Europe, and the DCFTA model may be what Turkey eventually has to settle for, if it doesn't decide that a sub-optimal relationship with Europe does not outweigh the benefits of a multi-vector trade policy, given its geographical position and robust pre-crisis economic growth. In Ukraine's case, the regression on democracy and rule of law may mean that it never fulfills the political criteria for a relationship with Europe. Belarus may already be beyond the point of no return having already joined the precursor to Putin's 'Eurasian Union'.

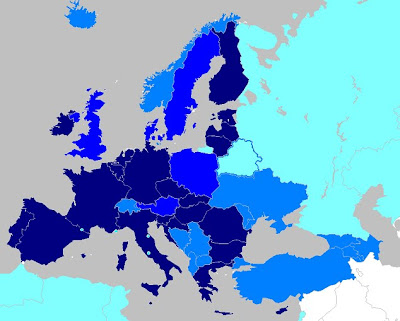

During European debates in the UK, going back to the 1990's, the phrase 'two-speed Europe' frequently came up, implying that France, Germany, Benelux, Spain, Italy etc. could push ahead with closer integration whilst, for example, Britain and the Nordic countries could take a slower approach. Only in one sense has this clearly manifested itself, but notably, in the EU states that did not choose to adopt the Euro. One might also sense that one or two newer EU members, longer term, might not desire the closest level of integration with other member states. Would Poland, for example, ever want to end up in political union with Germany?

So, if Britain is twitchy, Norway disadvantaged, Turkey rejected and Ukraine self-excluded, not to mention Switzerland and Iceland in Europe but not the EU, should these countries think about getting together in some kind of trade organisation, which could collectively lobby Brussels? If the EU had a rival club of 8-10 countries with which it had to agree single market conditions, might those countries together have real influence? In the longer term, such a consortium might be able to get Israel or Russia/Belarus/Kazakhstan on board and then you are talking about a rival group with tremendous clout. After all, if all these countries are either unhappy being under the EU's thumb, or given the cold shoulder by it, doesn't it make sense to look at other options? A looser organisation might also be able to more effectively involve Europe's southern neighbourhood.

There would be nothing to stop the group of non-EU members here (to list, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Turkey, Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova, Serbia, Macedonia, Montenegro) to sit down and discuss common interests and possible future co-operation. This is admittedly just an idea and hasn't been fully thought through, but perhaps not all roads in Europe lead to Brussels (?).

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment