Whilst the EU dropped the ball during Yushchenko's Presidency, is the present government just trying to play Brussels? If so, the results are increasingly farcical.

The Ukrainian President's recent trip to Cuba, against the background of the cancellation of an invitation from Brussels, could almost be taken as a marker of the country's fast track route to pariah status. Now even the Party of Regions' 'friends' in the Socialist grouping of the European Parliament are distancing themselves from the regime by backing a tough-sounding resolution on Ukraine due to be delivered in Strasbourg tomorrow. It's starting to look as if the European path was never Yanukovych's objective, or at least that they were never prepared to make any sacrifices in terms of their hold on power to achieve it. In conversations with government figures the mention of the EU-Ukraine free trade deal seems to get more of a philosophical sigh than a reaction of even qualified enthusiasm. It's also starting to look as if the EU is losing patience with what looks ever more like a circus that has little to do with the democratic gains the country made under the previous presidential administration. The EU must now be very wary of signing itself into an agreement with a regime which looks so eager to wreck its European credentials. Why should the EU allow itself to be used as a bargaining chip for Ukrainian oligarchs to haggle with Russia for cheaper gas for their cash cow steel and chemicals industries? Ukraine looks like it's becoming a feudalist state at breakneck speed.

There is no doubt that the EU's decision not to step in during the early years of Yushchenko's presidency with a clear path to the EU accession process will go down as a pivotal point in the region's history. We would undoubtedly be in a different position today had they done so. It was deemed necessary in the 80's to rescue Spain and Portugal from backsliding after their democratic revolutions and to rescue Greece from the Soviet bloc (despite the clear present evidence of their unreadiness for European integration, it was probably still the right decision). It was also the right decision to grant the former Yugoslav countries a distant but clear future direction. Understanding in society of European geopolitics is low at the best of times (just look at the UK!), and in somewhere like Ukraine particularly low. The Ukrainian public needed a clear and unambiguous signal that their eventual future lies with Europe, but in the end, the climate of cynicism in 2010 was enough to open the door to the Party of Regions who, it certainly seems, were only playing by democratic rules while it suited them. Just as with the Mediterranean and Balkan examples, as experts claim, there may be an enormous cost to the west from not taking in Ukraine, not to mention Moldova etc. from having a 'European Mexico' on the EU's doorstep, a disfunctional source of criminality and immigration.

But whilst the EU was to blame 5 years ago, the isolationism of 2011 is all of Ukraine's own making. The direction that Ukraine is going in might be better suited to joining the African Union than the European Union, and a glance at many of the indicators on corruption, business environment, rule of law and democracy simply confirm this.

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

Monday, October 24, 2011

Shades of Blue: Is there a European alternative to the Brussels project?

The post is from October, but the issue looks increasingly relevant.

As the EU struggles with its own well-documented problems, the UK has tied itself in knots by choosing today to debate and vote on the idea of a referendum on EU membership which is unlikely to happen after all three major parties put a three-line whip on the issue to vote down the proposal, which was triggered by the same pesky government e-petition website that threatened to throw open the debate on capital punishment.

British Eurosceptics are not a homogeneous group. There are the rabid 'bent banana' Eurosceptics who ignore the geographical reality of where our island sits, and for whom there is no distinction between EU migrant workers and illegal immigrants from elsewhere in the world. There are still some with delusions about the UK's potential global role, or farcical ideas that Americans or Australians would be 'delighted' to open up to preferential economic agreements with the UK. There is the frequently-coined argument that when Britain voted in the 1970's it voted to join an economic union, not a political one, but a look at the founding treaties of the EU makes clear that it was all along a politically-coloured project. Then there are quite reasonable arguments made about the democratic deficit in the EU's institutions. There is also the technical constitutional argument, which relatively few mention but which holds some water, about the incompatibility of the EU's system with the British system, that the British constitutional principle that 'no parliament can bind its successor' is broken by the signing of European treaties.

The main argument being given against the EU referendum seems to be 'now is not the time', which means that the issue in the long term is not likely to go away. Many people will continue to support Britain's withdrawal, saying things like 'look at Norway'. A Norwegian local politician I met a couple of years back however lamented her country's unwillingness to join the EU, saying that Norway has to implement 95% of EU legislation, with a 0% say about what goes into it. Very few who truly understand the issues think that Britain can simply have no form of economic integration with the EU. If Britain, for example, was to leave the EU, but desire to continue to participate in the single market, it would have to accept something similar to the EEA deal. Switzerland, on the other hand, has a series of bilateral opt-ins and opt-outs of EU policies, but on many issues it is captive to the regime that surrounds it.

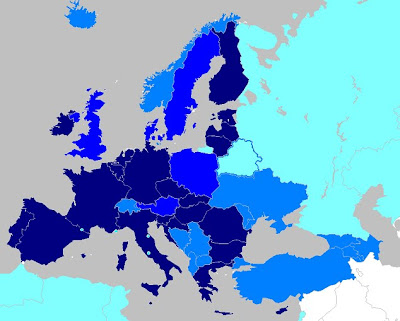

Britain, Norway, and Switzerland are not alone in feeling that their deals with Brussels are in some way unsatisfactory. Across Europe, on the eastern frontier, we have Turkey, the candidate country which may never join, which so far has only a customs agreement with the EU which is of limited value. Then there is Ukraine, which, whilst doing its best to shoot itself in the foot, has not yet formally abandoned its deep free trade area talks with the EU. Georgia and Moldova are likely to agree similar free trade deals with Europe, and the DCFTA model may be what Turkey eventually has to settle for, if it doesn't decide that a sub-optimal relationship with Europe does not outweigh the benefits of a multi-vector trade policy, given its geographical position and robust pre-crisis economic growth. In Ukraine's case, the regression on democracy and rule of law may mean that it never fulfills the political criteria for a relationship with Europe. Belarus may already be beyond the point of no return having already joined the precursor to Putin's 'Eurasian Union'.

During European debates in the UK, going back to the 1990's, the phrase 'two-speed Europe' frequently came up, implying that France, Germany, Benelux, Spain, Italy etc. could push ahead with closer integration whilst, for example, Britain and the Nordic countries could take a slower approach. Only in one sense has this clearly manifested itself, but notably, in the EU states that did not choose to adopt the Euro. One might also sense that one or two newer EU members, longer term, might not desire the closest level of integration with other member states. Would Poland, for example, ever want to end up in political union with Germany?

So, if Britain is twitchy, Norway disadvantaged, Turkey rejected and Ukraine self-excluded, not to mention Switzerland and Iceland in Europe but not the EU, should these countries think about getting together in some kind of trade organisation, which could collectively lobby Brussels? If the EU had a rival club of 8-10 countries with which it had to agree single market conditions, might those countries together have real influence? In the longer term, such a consortium might be able to get Israel or Russia/Belarus/Kazakhstan on board and then you are talking about a rival group with tremendous clout. After all, if all these countries are either unhappy being under the EU's thumb, or given the cold shoulder by it, doesn't it make sense to look at other options? A looser organisation might also be able to more effectively involve Europe's southern neighbourhood.

There would be nothing to stop the group of non-EU members here (to list, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Turkey, Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova, Serbia, Macedonia, Montenegro) to sit down and discuss common interests and possible future co-operation. This is admittedly just an idea and hasn't been fully thought through, but perhaps not all roads in Europe lead to Brussels (?).

Friday, October 21, 2011

2012 in Ukraine-walking the democratic tightrope?

In defining Ukraine's future, the Euro 2012 football championship looks like being a sideshow compared to the parliamentary elections which, if they go the President's way, may clear the political field for years to come. At the heart of this is the coming change to Ukraine's electoral system.

The proposal is for a mixed system, with half the deputies elected by party list and the other half by constituency mandate. Just like in Germany then, so that's all fine, or so the argument will go, rather like when people explain away post-Soviet autocracies as 'like the presidential system in France', conveniently failing to mention the liberal media environment, the French fondness for and tolerance of protests, strikes and direct action and, not least, democratic nuances such as the genuine Presidential Primaries currently taking place in the French Socialist Party. The assertions are short and snappy, but the counter-arguments require explanation.

The desire is, it must be believed, for a consolidated power vertical rivalling anything else in the post-Soviet space, but Yanukovych is walking a tightrope to a much greater extent than his counterparts in Russia or Belarus. Russia, because it does not aspire to any form of western integration (WTO membership aside). Russia's elections are carefully engineered through restrictions on registration of opposition candidates, high thresholds for entering parliament etc. In Belarus they just make it up, despite it being fairly certain in the past that Lukashenka could have won fair and square. Perhaps his currently plummeting popularity there suggests that, from his point of view, he made the right choice.

The difference with Ukraine is that its semi-democratic credentials are based on the sequence of free and fair elections, two parliamentary and one presidential, which took place under Yushchenko's much-despised stewarship. That means that Ukraine now has more to lose from western partners. We know they can do better. Therefore the maintaining of the Party of Regions' grip on power requires an approach certainly more subtle than in Belarus, and perhaps more ingenious than that in Russia. Yanukovych will never be able to pull off the United Russia trick, which relies on Putin's personal popularity.

The new law does not look like it will be the one to restore Ukraine's 'free' status that Freedom House stripped it of last year. To get into the nitty-gritty, the new law would take us back more or less to the system that was used in 1998 and 2002. The electoral constituencies will be formed just 90 days ahead of the elections. Were this knowledge, heaven forbid, to be available to the powers that be in advance of that date, they would be able to steal a march on the opposition in terms of strategic planning. The election commissions would be formed of the parties in power, so the Party of Regions and the Communists. Party lists will be able to be changed even on election day itself. Appeals will be impossible in practice because the deadline will have expired while the documents are still in the post. And so the list goes on...

But it may not be these technical aspects that lead to a democratic malfunction in 2012, but rather two important cultural aspects. Firstly, that whether or not the President is trying to steer Ukraine down the European path, much of his support base has clearly taken his coming to power as a return to the 'good old days'. That means back to the days when ballot boxes are loaded into trucks or thrown in rivers. I'm not sure Ukraine's leadership will be able to prevent widespread abuses even if it wished to, because the prevailing culture is now the pervasively undemocratic post-Soviet one. There's no real understanding in those circles of the value and importance of respecting the rules.

The second cultural aspect rests with the electorate. It has been found that, particularly amongst the young, there is a despondency about the whole exercise and a willingness to sell their vote for 100-200 dollars. It has also been noted by researchers that trust in Ukraine's judiciary has plummeted over the last year and a half. There is little hope of successfully challenging any violations. Having said that, interviews with the public have thrown up some quite reasonable suggestions-that deputies who do not attend parliament should be fired or not paid, that each voter should have a stamp confirming that they've already voted put in their internal passport (the Sovietesque Ukrainian national identity document) to prevent multiple-voting and the banning of deputies elected on lists from crossing the house. But in the end, whilst both the general population and the elites have plenty to say on what should be amended in the new law, there is clearly a fundamental disconnect between any of these people and the decision-makers, who have probably already decided what they want.

The elections will almost certainly take place in the restricted media climate that has come to exist in recent times. And in any case, following the elections it's difficult to say what the point will have been, given the deterioration of procedural standards in the Verkhovna Rada, the 'piano-players' voting for absent deputies, use of physical violence, blocking of the rostrum by the opposition etc. And presumably if the result is not quite the desired one, the Constitutional Court will allow a few 'tushki' to cross the house and make up the numbers.

Events may anyhow overtake things. Relations with the west are deteriorating rapidly and, in the worst case scenario, the incentives for democratic good behaviour may have all but evaporated by then. In any case, the EU is, for all its faults, a community of shared values, and if these values are not in evidence in Ukraine, one could say, what is there to discuss?

The author attended Civic Discussion of Parliamentary Election Law of Ukraine on 19th October 2011 http://kyivweekly.com.ua/accent/news/2011/10/13/144855.html

The proposal is for a mixed system, with half the deputies elected by party list and the other half by constituency mandate. Just like in Germany then, so that's all fine, or so the argument will go, rather like when people explain away post-Soviet autocracies as 'like the presidential system in France', conveniently failing to mention the liberal media environment, the French fondness for and tolerance of protests, strikes and direct action and, not least, democratic nuances such as the genuine Presidential Primaries currently taking place in the French Socialist Party. The assertions are short and snappy, but the counter-arguments require explanation.

The desire is, it must be believed, for a consolidated power vertical rivalling anything else in the post-Soviet space, but Yanukovych is walking a tightrope to a much greater extent than his counterparts in Russia or Belarus. Russia, because it does not aspire to any form of western integration (WTO membership aside). Russia's elections are carefully engineered through restrictions on registration of opposition candidates, high thresholds for entering parliament etc. In Belarus they just make it up, despite it being fairly certain in the past that Lukashenka could have won fair and square. Perhaps his currently plummeting popularity there suggests that, from his point of view, he made the right choice.

The difference with Ukraine is that its semi-democratic credentials are based on the sequence of free and fair elections, two parliamentary and one presidential, which took place under Yushchenko's much-despised stewarship. That means that Ukraine now has more to lose from western partners. We know they can do better. Therefore the maintaining of the Party of Regions' grip on power requires an approach certainly more subtle than in Belarus, and perhaps more ingenious than that in Russia. Yanukovych will never be able to pull off the United Russia trick, which relies on Putin's personal popularity.

The new law does not look like it will be the one to restore Ukraine's 'free' status that Freedom House stripped it of last year. To get into the nitty-gritty, the new law would take us back more or less to the system that was used in 1998 and 2002. The electoral constituencies will be formed just 90 days ahead of the elections. Were this knowledge, heaven forbid, to be available to the powers that be in advance of that date, they would be able to steal a march on the opposition in terms of strategic planning. The election commissions would be formed of the parties in power, so the Party of Regions and the Communists. Party lists will be able to be changed even on election day itself. Appeals will be impossible in practice because the deadline will have expired while the documents are still in the post. And so the list goes on...

But it may not be these technical aspects that lead to a democratic malfunction in 2012, but rather two important cultural aspects. Firstly, that whether or not the President is trying to steer Ukraine down the European path, much of his support base has clearly taken his coming to power as a return to the 'good old days'. That means back to the days when ballot boxes are loaded into trucks or thrown in rivers. I'm not sure Ukraine's leadership will be able to prevent widespread abuses even if it wished to, because the prevailing culture is now the pervasively undemocratic post-Soviet one. There's no real understanding in those circles of the value and importance of respecting the rules.

The second cultural aspect rests with the electorate. It has been found that, particularly amongst the young, there is a despondency about the whole exercise and a willingness to sell their vote for 100-200 dollars. It has also been noted by researchers that trust in Ukraine's judiciary has plummeted over the last year and a half. There is little hope of successfully challenging any violations. Having said that, interviews with the public have thrown up some quite reasonable suggestions-that deputies who do not attend parliament should be fired or not paid, that each voter should have a stamp confirming that they've already voted put in their internal passport (the Sovietesque Ukrainian national identity document) to prevent multiple-voting and the banning of deputies elected on lists from crossing the house. But in the end, whilst both the general population and the elites have plenty to say on what should be amended in the new law, there is clearly a fundamental disconnect between any of these people and the decision-makers, who have probably already decided what they want.

The elections will almost certainly take place in the restricted media climate that has come to exist in recent times. And in any case, following the elections it's difficult to say what the point will have been, given the deterioration of procedural standards in the Verkhovna Rada, the 'piano-players' voting for absent deputies, use of physical violence, blocking of the rostrum by the opposition etc. And presumably if the result is not quite the desired one, the Constitutional Court will allow a few 'tushki' to cross the house and make up the numbers.

Events may anyhow overtake things. Relations with the west are deteriorating rapidly and, in the worst case scenario, the incentives for democratic good behaviour may have all but evaporated by then. In any case, the EU is, for all its faults, a community of shared values, and if these values are not in evidence in Ukraine, one could say, what is there to discuss?

The author attended Civic Discussion of Parliamentary Election Law of Ukraine on 19th October 2011 http://kyivweekly.com.ua/accent/news/2011/10/13/144855.html

Friday, October 14, 2011

Is this what it takes to get Europe's attention back on the east?

The sight of the forlorn Tymoshenko on newspaper front pages across the world has arguably given Ukraine the most exposure that it's had since the Orange Revolution. At EU level, it was telling that a europarl news item on a European Parliament plenary session which would have read 'MEPs to debate Middle East uprisings with Catherine Ashton' now read 'MEPs to debate Middle East uprisings and sentencing of Ukrainian opposition leader with Catherine Ashton'. Is this what it takes to get the EU's attention on to the problems on the eastern half of its own continent, rather than on Europe's external periphery. The willingness to prioritise emerging democracy in the southern neighbourhood over its survival in the eastern neighbourhood might have proceeded undeterred were it not for this very serious wake-up call.

Even more than Europe's diplomatic shortcomings, the Ukrainian President now seems to have come up with a spectacular inverted version of the famed 'yes man' Kuchma diplomatic policy, having managed to disenfranchise not only the Unites States and European Union, but Russia as well. Indeed, that the conviction centres on a gas deal countersigned by Russia's all-powerful de facto President is a prickly point, and it's very possible that the Russian Prime Minister considers it a personal slight (Putin has apparently said that he doesn't like Yanukovych, add to the well known fact that he 'personally detests' the Belarusian President Aleksandr Lukashenka-politics in this part of the world is always personal).

The world's newspapers have perhaps got the wrong idea. Tymoshenko is no Aung San Suu Kyi, even if the Ukrainian judiciary risks turning her into one in the eyes of many. It has been more soberly pointed out in some quarters that the 2009 gas deal did contain some quite serious violations. But these violations were made at a time of extraordinary pressure on the Prime Minister. Both Russia and EU states seem to be rather forgetting their roles in what transpired that January as a result of Russia shutting off the gas taps. They are also largely based on Soviet era laws, as is the precedent for the curious practice of a personal fine levied for a loss to the state budget. After all, nobody has claimed that Tymoshenko has personally helped herself to funds from the gas deal. What even happened to the Kyoto money we were talking about when she was first charged?

It's also in a sense not the point. Tymoshenko's party is the only genuine opposition left in Ukraine. Commentator Taras Kuzio claims that every other party feeds dierctly or indirectly into the Party of Regions power structure. Like Khodorkovsky in Russia, dismissed by many as 'no angel', the most obvious casualty is that of political pluralism in the state. It's doubtful that Tymoshenko has really been put away for technical reasons. Amongst various theories, one suggestion was simply that the President is sick of her endless ex-con jibes.

The news that further charges are going to be leveled against Tymoshenko is hardly going to help curry favour abroad. The new charges, of direct personal enrichment, are perhaps more to the point, but I would steer clear of that one, at risk of creating a precedent for looking into the ill-gotten gains of one's predecessor's personal enrichment following their fall from power.

So now we see a diplomatic squeeze on Ukraine from outside, but at the same time a domestic squeeze on Ukraine's population. New currency exchange laws and bans on loans in foreign currency are a case in point. Indeed, the new currency exchange rules have lead to currency exchange booths in central Kiev turning away foreign customers altogether. With Kiev's newly-renovated Olympysky Stadium set to host a friendly between Ukraine and Germany in November, one has to wonder how any Germany fans brave enough to make the trip are going to get on. Most likely, we'll see a facade similar to the one Russia put on when it hosted the 2008 Champions' League final, where the visa requirement was temporarily dropped to prevent the embarrassment of 70000 Brits queueing for Russian visas, and the notorious Russian police were suddenly immaculately-behaved, for 48 hours or so. It will be a great shame if Euro 2012 next summer turns out to be a similar cosmetic exercise rather than a lever for change and a chance for the country to adopt European norms in many areas. It has been suggested that the new currency rules are in fact a data-collecting exercise on the country's citizens which will soon be complete, for some unknown purpose.

On the subject of sport, an interesting aspect of the Tymoshenko detention is that it leaves a vacancy for opposition figurehead that may be filled by one of Ukraine's most popular public figures, boxer Vitali Klitschko, who has been boosting his media profile of late. Although he did not previously succeed in two attempts for the Kiev mayoral office, he has the distinct advantage that, unlike almost all the alternative figures in Ukrainian politics, Klitschko did not get to his present position through corruption. His time living in Germany also gives him a different perspective on how the country should be run. There are big question marks about how politically able he is, and whether he can overcome a fair amount of public scepticism about his ambitions, but if he surrounded himself with the right people he would certainly do no worse than the current incumbent, and might be the one to finally knock some heads together!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)